Korcula and Split, Croatia

Korcula Island is 29 miles long and between three and five miles wide. It has a 2,000-foot mountain that runs from one end of the island to the other, like the fin on a fish’s back. The town is situated on the northeastern portion of the island. It is toy town that has, like all of the coastal towns in the area, been the site of human inhabitants since Neolithic times. We are in and out in a few short hours.

The Opatska Riznica (Abbey Treasury) is surprising. Here is an exhibit containing a small drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, a larger one by Raphael and two sketches by Tiepolo, one of which is a large head at the top of the entrance way. The collection also includes a large number of seals once belonging to Austrian Jews. I ask the guide where they came from. She says they were a gift. I take that to mean they were stolen.

In the Cathedral of St. Mark next door you can also see two early paintings by Tintoretto. The statuary compares with those you see on the Italian mainland, including an impressive Pietà. On a wall are trophies that herald the participation of Korcula in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. All of this suggests Korcula’s close ties to the Venetian mainland. This is, of course, not unique to Korcula. In the Maritime Museum in Kotor there were models of the St. Tryphon, a Korculan vessel, that fought at Lepanto.

The Battle of Lepanto is one of the great sea battles of history. It was also one of the bloodiest. The Christian League, to which Korcula and Kotor contributed, lost 15,000 men. The Turks lost twice that number – 8,000 Turks were taken prisoner. On the plus side, 15,000 Christian galley slaves were freed. The hero of Lepanto was the Spanish sea captain, Don Juan; the anti-hero, the Italian Gian Andrea Doria, whose cowardice and bad seamanship, in the words of John Norwich, almost cost the Christian League the battle. Miguel de Cervantes, author of one of the greatest novels in western literature, Don Quixote, fought at Lepanto, was wounded in his left hand, and acquired a life-long nickname, The Cripple of Lepanto.

From a geo-political point of view, the battle didn’t amount to a great deal. The Turks weren’t beaten back forever but resumed their westward onslaught. Within three years they had driven the Spanish out of Tunis and had turned the area into an Ottoman precinct.

The real significance of the battle of Lepanto lay in how it changed, thanks to the creativity of Don Juan, the conduct of naval warfare. Don Juan introduced the hitherto unheard of tactic of placing cannon on the deck of a ship. It was a tactical move that spelled defeat for the Turkish armada. It was, in fact, so successful a maneuver that all future naval warfare would be conducted at long distance. No more swashbuckling sword fighting, mano a mano. This meant bigger sailing ships and fewer galleys. The days of Errol Flynn ramming the enemy and grappling with them were over. Modern naval warfare had begun.

A concert by an acapella quartet of islanders from Vela Luka, the other town on the island, takes place inside All Saints Church. The musicians all have day jobs. One is an electrician, one an ex-seminarian – a guitar player who went into the seminary and fell in love with a nun, who fled with him to the secular side of life – and an undertaker.

Marco Polo may or may not have been born here. Doubt notwithstanding, they are building a museum to him and his family at the alleged homestead behind the Cathedral.

After lunch we sail to Split where we split into two groups – one to the archeological site at Solin, the other to the Palace of Diocletian. I choose Diocletian, the first emperor ever to resign from office.

Diocletian must have had retirement in mind for at least ten years – the time it took him to build his palace at Split, the city the Romans called Spalato. Split is a better name. It was – in that domino fashion one so often finds in history – Diocletian who was responsible for the division of the Roman Empire into the East (Constantinople) and the West (Rome). Having decided that the Empire was too large for a single ruler, he imposed the so-called tetrarchy, the rule of two Augusti: he and his companion-in-arms, Maximilian, in 285 and then two Caesars, Galerius and Constantius Chorus, eight years later. The latter was the father of Constantine I, the emperor who defeated Maxentius in Rome in 312, within a year of the death of Diocletian

himself.

It was Constantine I, of course, who moved the capital of the Empire from Rome to Constantinople where it remained as competitor to and thorn in the side of western Christianity for over a thousand years, until its fall at the hands of the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

By the time of Constantine’s triumph, Diocletian had been out of power for seven years. His death went unnoticed. At one point, three years after his abdication, he was offered the mantle of Augustus again. His reply is famous: “If you could show the cabbage that I planted with my own hands to your emperor, he definitely wouldn’t dare suggest that I replace the peace and happiness of this place with the storms of a never-satisfied greed.”

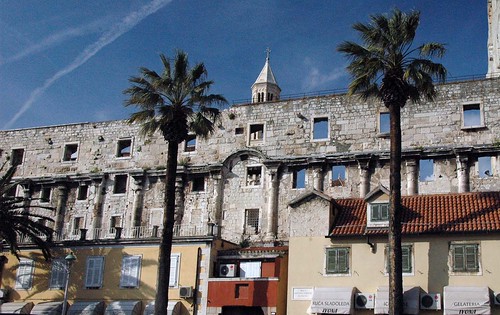

Bright stars and black stains mark the reign of Diocletian. He is the emperor who brought order to a disintegrating Empire, at least for a time. He is also the author of four edicts leading to the last and worst of the persecutions of the Christians. Walking toward his palace, I see the shape of the seaward wall of the great building still visible behind the cafes and shops that have attached themselves to it like barnacles to a hull.

As we approach the palace, Bill Ross observes that cities consume their past. He has put it very well. How many cities have we visited that have, in fact, been built on top of cities? The practice resembles that of the inhabitants of the ancient city of Enkomi on the island of Cyprus whose inhabitants buried their dead beneath them in the very houses they were living in. Their dead were just downstairs.

Diocletian’s Palace at Split is different, but not, a la Monty Python, completely different. Much of the palace has disappeared. But the Temple to Jupiter has been reshaped into the Baptistry of St. John. There is a Mestrovic statue of John looming over the baptismal font. The Mausoleum of Diocletian is now the Cathedral of St. Domnium. New gods for old.

The walls of the palace have been incorporated into the modern life of the town the way an artificial limb is incorporated into a body. I take this to be a metaphor of the way things ought to change, not cataclysmically, but in tiny increments.

As you pass through the Silver Gate into the high-vaulted rooms of the ancient palace,you are actually looking at the basement. These rooms were either used for storage or nothing at all. They were there to absorb the rising and falling waters of the Adriatic leaving the living space above them high and dry, literally. The workmanship of the rooms is extraordinary. The stone blocks of the walls are as tight fitting as Spandex.