Sunday, April 11, 2009

Sicily was a virtual Times Square of the ancient world. At one time or another practically everybody who was anybody came here, albeit with blood in his eyes. Everybody and her brother had won or lost a piece of the place. Syracuse is as good an illustration as any. Founded as a Corinthian colony in 734BC, about the same time that Corinth invaded Corfu, within a century it rivaled Athens in power and prestige. That, of course, meant enemies.

Threatened alternatively by the Athenians, the Carthaginians and the Romans, Malta’s early history was one war after another. What made it war worthy is reflected in its celebrities. In the fifth century, Aeschylus and Pindar worked here. When the city fell to the Romans in 212BC, Archimedes was killed here. St. Paul slept here.

The presence of Archimedes in Syracuse made it all that much harder for the Romans to conquer the town. One of Archimedes inventions was the Architronito or steam cannon. At one end of a barrel was a chamber filled with rocks. When the rocks were heated, steam generated by dousing them with water propelled a stone ball the length of six football fields. The Romans wanted Archimedes captured alive. Instead a Roman soldier ran him through while he was doing math in the sand.

The centerpiece of Syracusan ruins is a part of the Regional Archeological Museum. An amphitheater 453 feet across and, at its largest, 59 rows high, it was built by the Greeks in 475BC and enlarged in 230BC. Aeschylus' Persai (The Persians), an account of the Greek victory at the Battle of Salamis in 480BC, was premiered here in 472BC. The battle had taken place a mere eight years earlier.

A mountain stream brings fresh water into the upper reaches of the amphitheater. The third balcony as it were. One can easily imagine the Syracusans moving back and forth between the fountain and the play. Like the Japanese Noh theater, these spectacles went on for days. Our guide thinks the fountain’s main purpose was to provide inspiration for the actors, rather like a watercooler to officeworkers. Maybe. Her guess is as good as anyone’s.

Behind the theater is the stone quarry. It was used to build, not only the superstructure of the amphitheater—its seats were carved out of solid rock, which is why they have survived until today (you can't steal a mountainside)—but everything else in the vicinity, the houses, temples, the administrative buildings. It was also used as a concentration camp.

According to Thucydides at one time 7,000 Athenians were imprisoned here. They would have been herded into a black hole hewn out of the rock by stonecutters. Today, the roof has long since caved in. It looks more like a rock garden for giants than a prison.

One cavern of the quarry remains undamaged. Called Dionysius Ear because of its remarkable acoustic properties—you can hear a whisper at one end when you are standing out of sight at the other a la the whispering scene in La Dolce Vita—the guides are filled with complicated stories about the genesis of this cavern. They call it the amphitheater’s sounding board and explain that it was left this way in order to amplify the voices of the actors in the amphitheater next door. Our guide is dubious and so am I. The hole at the top of the cavern is much too small to allow the cavern to resonate. When we visit the amphitheater itself, workmen have begun to hide the stone seats beneath wooden covers to protect the stone itself and the 1,000 person per night audience coming to see Medea, Oedipus and The Eumenides.

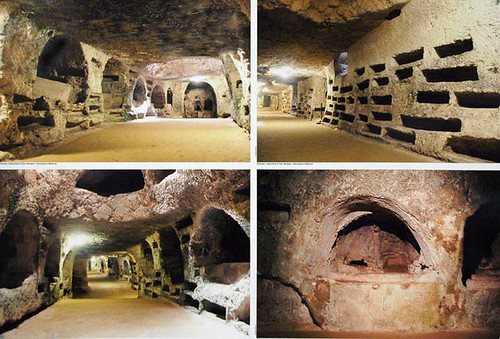

We bury our dead in as many imaginative ways as we kill one another. In the catacombs of Syracuse, 25,000 souls were interred in pigeonholes. It is like a battery of post office boxes for dead bodies.

It is often said that death is the great leveler. Not so. The catacombs were strictly reserved for Christians. Even in death birds of a feather flock together. This only goes to show that how we bury our dead is not, in fact, for the dead but for the living. Our guide describes how one tomb has three holes drilled into its top slab in order to allow milk and honey to be infused in the grave in hopes of awakening the dead. As someone out of the crowd remarked, “It didn’t work.”

I find catacombs a bit on the far side, though not as far out as, say, the practice of the Capuchin monks in Rome who take the bones of dead brothers and fashion them into altars, clocks, crosses, and other pieces of ecclesiastical furniture. The designs are inspired. You can see them on display in Rome beneath the Capuchin monastery and church on the via Vittorio Veneto near the Piazza Barberini.

By far my favorite way of burying the dead is on display at University College, London. There you can find its benefactor, the great utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, not in a pigeonhole or a crypt or in the shape of a writing desk. Rather, he is sitting upright in a glass cabinet, stuffed where he needs to be and clothed as he was when he walked the streets of London in the 19th century. His real head is in a tin box under his chair. At least it used to be. The probably apocryphal story I heard when I was teaching there was that it fell off when a heavily loaded lorry drove by. Today a wax replica sits on his dead neck, well hidden by a high collar, and, if I remember correctly, a broad brimmed light brown hat shades his waxen head. The university officials keep him in a cabinet in a corner of the main building. If you ask the beadle outside the Provost’s office to wheel Jeremy out into the open, he is obliged by Bentham’s will to do so. Bentham meant his last remains to be an anti-religious piece of propaganda. He called it an “auto-icon.”

There are two things about the island of Sicily that have surprised me. The first, of course, was the ruins themselves; they are ubiquitous, suggestive, sad and, in many instances, incredibly beautiful. I think the temple at Segesta, for example, is better than anything I’ve seen in Greece save the Parthenon. The second is the ruinous metropolises that have grown up around them.

Palermo, once one of the most beautiful cities in the world, has been obliterated by the Mafia-inspired building surge that is remarkable as much for its origins as it is for its execrable taste. In Agrigento a revivified Mafia has done the same. Ditto in Catania. Ditto Syracuse, another city overrun by a scabrous architecture. Now a new modern French designed cathedral adds insult to injury. Its dome rises above the rooftops like a grey concrete teppee. I ask Leanna, our guide, what the people of Syracuse think of it.

She asks if there are any Frenchmen among us. Then she says, “We don’t like it.”

Neither do I. Leanna is gracious. She points out how the French hated the Eiffel Tower and now it is that country’s icon.

“Maybe it will turn out to be really good,” she says.

Only Ortigia seems to have emerged unscathed from the architectural plague of the 1950‘s on.

This gorgeous headland at the tip of Syracuse, in fact, the site of the first settlement 2700 years ago, is a beautiful oasis in a sea of cheap cement. In its center is the Syracuse Cathedral, built on the site of a Temple to Athena erected in the 5th century BC. In the 7th century AD Bishop Zosimus converted it into a church, perhaps to celebrate the defeat of the Carthaginians in 480BC by Theron of Agrigento and Gelon of Syracuse. The columns of the original temple are visible. The stonework of the church has simply enfolded them. It is a remarkable example of how, in order for a temple to survive, it became a church. It was this transformation that saved the superb Temple of Concord in Agrigento.

If you are married in Ortigia because you have the great good fortune to come from there, where, I wonder, do you go on your honeymoon? Ortigia has barely been touched by the Mafia generated building blight and now it looks as if it won't be. The boom has stopped. This is not because Sicily has run out of people to build houses for. Rather it is because the French connection collapsed in 1970. When Marseilles was busted, the Sicilian Mafia picked up the heroin trade. Here is a corroborating statistic. In 1974 eight Italians OD'ed on heroin. By 1980 Italy had 200,000 addicts, hundreds of which died each year. In 1989, for example, the number of deaths was 951. So the Mafia got out of the house business and into drug trafficking. Good for the città, bad for the cittadino.

Two things happened in Syracuse that stick in my mind. The first involves the Emperor Constans II who, in 663, decided to move his capital back to the west from Constantinople. He had tried Rome but found it much too much of a backwater. He preferred Syracuse so he moved the Byzantine capital there. He ruled the Empire for five years until, according to John Julius Norwich, “a dissatisfied chamberlain, in an access(sic) of nostalgia, surprised him in his bath and felled him with his soap dish.”

The second concerns Archimedes who, charged with finding out whether a crown was pure gold or not, hit upon the idea of testing the suspect crown by the amount of water it displaced compared to the displacement of the real thing. The idea struck him while he was taking a bath. He was reputed to have run home from the bath house, completely naked, yelling “Eureka,” I have found it.

If anyone believes this, I have some stock guaranteed at an annual rate of 10% to sell him.

We leave Syracuse at 12:30pm on the dot bound for Albania. We are headed out into the Ionian Sea where a Force 8 gale on the Beaufort scale awaits us. This means six to eight foot seas and thirty to forty knot winds.

Everyone on board is reeling from wall to wall like drunks at a New Year’s Eve party. The crew has helpfully distributed barf bags at convenient distances along the handrails of the corridors, convenient meaning one barf bag every three feet. Only twenty people show up for dinner. Everyone else is either lying in bed or barfing in a bag. And people wonder why I describe myself as a reluctant traveler.

Nancy is one of those in bed. She started feeling queasy about 4 o’clock. I checked in on her about six. She wanted something light to eat. The staff said we could order something in our room. She has a salad, soup and ginger ale. I have roast beef, onion soup, shrimp cocktail, salad, two rolls with butter and tea, the whole nine yards. I don’t get seasick and I’m feeling pretty smug about it. It’s just about then that the ship takes a deep breath, holds it for a few weightless seconds, then lets it out in a starboard roll that dumps the dinner, plates and all in my lap. And people wonder why I describe myself as a reluctant traveler.